Chapter X

The Tampico Disaster

In September, 1955, killer Hurricane Hilda hit Tampico,

Mexico.

Ferree, uncanny in his ability to foresee what was com-

ing, was on top of developments from the beginning. He

had begun to prepare himself while the storm was still at

sea, asking for large orders of medicines, food, and clothing

from his sources around the country, knowing that he

would need them by the time they arrived in the Valley.

When Hilda slammed into the Mexican coast, reports

coming in from Tampico showed Frank's worst fears to be

well grounded. He would need all the help and supplies he

could muster.

The buildings of downtown Tampico were battered and

torn by the winds, the streets became raging torrents of wa-

ter. Dogs, pigs, and horses swam vainly against the cur-

rents in city streets.

First reports listed 183 known dead, with another 370

persons assumed dead. The Panuco and Tamesi Rivers rose

rapidly. Then, to make matters worse, the Mexican weather

bureau reported storms building up in both the Pacific and

Gulf regions which would pour more water into the flooded

zone.

Tampico, itself, was reported to be in complete havoc.

-- 41 --

Frank Ferree got on the phone with the Mexican

governor's office at the inland city of Victoria just before the

lines went down. A secretary said Governor Horacio Teran

was already in Tampico where all classes of aid were des-

perately needed helicopters, rubber boats, food, medicines.

Ferree, never one to fool around after he'd sized up a

situation, got on the phone to Fourth Army Headquarters

in Fort Sam Houston, Texas. His friend and helper, Lt.

Eric Johnsons stationed at Harlingen Air Force Base, ver-

ified the need of aid to officials at Fort Sam Houston.

Fourth Army officials called Washington, then told

Ferree that the Mexican government would have to

officially request aid. Ferree called the Mexican Counsul

General Rafael Aveleyra, acting ambassador, who im-

mediately requested aid of the American government.

By the time Ferree and Lt. Johnson could get to the

Brownsville airport some fifty miles away, they saw three

helicopters coming in for a landing, the vanguard of a vast

relief mission which eventually included the aircraft carrier

Saipan. The flat top, anchored of Tampico, sent in helicop-

ters loaded with food and medical supplies to aid flood vic-

tims in remote areas.

Helicopter pilots brought back first-hand reports to

Ferree that one-third of the city was under water, with only

tops of telephone poles visible in some areas. The copter

pilots had set up a base at Tampico airport and had begun

dropping family packages of food and clothing to families

stranded on small islands of land throughout the city. They

kept this up for a week. The relief packages consisted of

canned milk, fresh bread, flour, beans, and small medical

aid kits.

Ferree wired the Mexican ambassador again, asking

him to request 100 rubber boats and 5,000 blankets from

American officials. Within hours a cargo plane with boats

and blankets left for Tampico.

The base of operations of the rescue mission was

moved from the Brownsville airport to Harlingen Air Force

-- 42 --

Base, some two miles east of Frank's shack. From this new

base an average of sixteen cargo planes left daily for Tam-

pico.

Finally, the hurricane, going inland, broke up against

the mountains, causing prolonged flooding along the Panuco

River which flowed back to the Gulf through Tampico and

surrounding areas.

Rear Admiral M. E. Miles, Navy Relief Director for

the area, said he had never seen a disaster of such propor-

tions. Officials feared the death toll would rise to even

more terrible proportions by the new surges of water in the

Panuco and Tamesi. I

Thousands of refugees from the port city of 160,000

jammed the airport and begged helicopter pilots to "fly us

out of here."

Officials reported that the majority of isolated persons

were slowly starving and sick with malaria and typhoid.

Ferree worked day and night. Never had he been so

busy. He got hold of a vitamin food supplement called

"Meals for Millions" which was shipped in from a California

foundation. One gallon of this supplement provided a

glanced meal for twenty-six people at the cost of only

three cents per meal. He shipped thousands of gallons of

the supplement and distributed it without charge to Tam-

pico victims.

A few weeks after the disaster, Governor Horacio

Teran of Tamaulipas State, in appreciation for Ferree's as-

sistance during the hurricane, presented him with a gold

medal.

Governor Teran, accompanied by a party of fifty, in-

cluding his cabinet members, was escorted across the

Brownsville International Bridge by a Texas delegation con-

sisting of Texas Governor Allan Shivers and dozens of Val-

ley mayors and Chamber of Commerce officials. Teran and

his party were entertained at a barbecue dinner, then ap-

peared on a Harlingen TV station to thank the American

people for their great aid during the disaster. It was then

that he presented Ferree with the gold medal.

-- 43 --

Chapter Xl

The Daily Routine

Ferree's day starts before daylight. It ends about ten at

night after he's prepared his old truck for the trip next day

by loading it with supplies.

Mondays, he goes to Matamoros; Tuesdays to Reynosa.

Wednesdays he stays around Harlingen, moving through

the back alleys as he scrounges day-old bread, wilting fruit

and vegetables, soup bones, used soap from motels, old

newspapers, scrap lumber. Then back to Matamoros on

Thursday, more scrounging in Harlingen on Friday, and to

Reynosa on Saturdays. Sundays he tries to rest, "like the

Bible says to do."

At first his lifestyle offended his fellow citizens,

perhaps because they thought he had an ax to grind or a

gimmick of some kind. Many considered him just a harm-

less old bum who would someday go away. "Kind of crazy,"

some of them said about him. In time, though, they began

to recognize hiS organizational abilities and his dedication to

helping the poor.

"We finally realized he is our most distinguished citi-

zen," a local businessman said. "We'd had a truly holy man

among us all these years without realizing it.

I went with Ferree many times to observe him at

work. On a typical day we went to one of the makeshift

-- 44 --

clinics in Reynosa. Our truck was loaded with medicines

and vitamins he'd coaxed from a national drug company.

Sometimes, in Mexico, he gives inoculations if none of the

volunteer Mexican doctors are available.

As we arrived at the clinic, young and old came out to

shake hands with El Amigo, the friend. The distribution of

food and supplies was done with dignity. Some of the usual

helpers are boys and girls who have been operated on and

cured of birth detects through Ferree's mediation with sur-

geons.

Older women helped give out the food and clothing.

They knew who should get the precious meat, which

mothers with suckling babies most needed the big bottle of

orange juice; just how much and what kind of food this man

with ten motherless children needed.

After things are organized and going smoothly, Ferree

usually begins to watch for children who have major physi-

cal problems. If he finds one, he will later go to talk to his

more influential friends on both sides of the border, giving

them details of the case, sometimes taking the child along,

asking until they give in and pay for an operation or what-

ever is needed.

At the lunch break, Ferree picks an orange, a banana,

and a crust of bread for himself: "I remember when I first

started out," he said. "I walked through the poorest areas

on both sides of the river, carrying a knapsack with what

food I could buy or beg. As a matter of fact, the army

surplus store gave me the knapsack. I wore out six or eight

of them. Anyway, I discovered there were many children

along the river who were almost blind with an eye infection

of some kind. I couldn't practice medicine on the U.S. side,

but I could on the Mexican side, so I got to mixing penicil-

lin in salve and treating those children's eyes. That's how

my medicine program got started."

"I've seen Frank deliver babies in his shack at I Har-

lingen, said Gale Armstrong, a plumber who is one of Fer-

ree's long-time American volunteers. "The door to his shack

-- 45 --

is never locked and nobody is ever turned away

A mother came to him with a boy about seven. At

her command the boy jumped around th show how he

could move. Then she pulled up his shirt and showed a

long scar where surgeons had operated on his spine "He

could't get out of bed until the operation," she said and

pointed to El Amigo as the man who brought it about.

Through Ferree's efforts, several hundred crippled

children have heen examined and operated on by surgeons

in Monterrey, Mexico, and in Houston, Texas None of the

patients could pay for the surgery, treatment, braces, new

clothing, toys, hospital expenses, transportation and other

expenses But Ferree's persuasive powers raised the cash

and found the skills.

Today he'd found a girl whose finger had grown to the

palm of her hand, and tomorrow he will take her over the

bridge with customs officials' permission, so she can get an

operation from a Harlingen physician.

Late in the day Ferree closed his clinic and, after visit-

ing the city jail, we went to the Mexican state prison far-

ther down the river, where prisoners live in squalor and

depravity.

The guards knew Frank and they allowed him to enter,

wllere he attended to the sick He then doled out loaves of

bread, a few old soup bones to make a big pot of soup in

the prison yard. As it was near Christmas he brought them

bags of Christmas candy, tied up in little plastic bags with

an apple and an orange.

-- 46 --

Chapter XII

The Albert Schweitzer of the Rio Grande Valley

After the day's work, we sat around the big barrel stove in

his shack and Frank threw old newspapers through the hole

in the side of the stove. Chuckling at the use he's found for

the daily rag's drivel, he closed the door and placed a

couple of pieces of bread on top of the drum. When they

had warmed, he took them off and handed one to me

keeping one for himself.

"You eat them, Frank," I said. "You did all the hard

work today. You need to eat a good supper to keep up your

strength."

But Ferree declined. Holding out the bread to me, he

said: "I got all I need."

As I ate the bread, I looked around the shack. There

was no radio or TV set in the building. My gaze went back

to Ferree.

The man was uncanny. I le did not worry about

whether he was selfish or unselfish, or whether he was

good or bad, or whether people liked him or hated him.

He simply wanted to help when he saw someone in

need. He just kept hammering at it until he did help, until

he provided whatever it was the suffering person needed to

help him feel better, be it medicine, money, food, clothing,

shelter, or whatever.

-- 47 --

"You know," Ferree said, "Jesus said help the poor.

Lots of people torget that now. But that's what Christianity

is, helping the poor, helpillg those in need. Everybody had

forgotten that teaching."

I stared at the man. He lived in litter and pieces of

junky furniture that someone had tossed out. He pulled it

Out of the trash, worked on it a little, tightened it up,

nailed it back together, covered it with a new piece of

material, and kept it in his house until he could find some

newlyweds who needed it.

He dressed in rags. He gave away better clothes than

he wore himself: Once I knew a Harlingen businessman

who had met him downtown on a cold winter's day. An an-

cient army overcoat draped his slim bony shoulders, hang-

ing to his knees. Later, the same businessman found him

scurrying around picking up day-old bread, but without the

overcoat, and in shirtsleeves.

''What happened to your overcoat?" he asked.

Ferree looked up as if it was a matter of little concern.

"Oh, I found a man who needed it worse than I did so I

gave it to him," he explained.

As I studied him, the man seemed inadequate to his

important and life-giving work. His ears and nose were too

big, his voice gravelly, scratchy, and watery.

"People give me everything I need tor myself and the

program he said. "Everybody can't do well are work, but

they give what they can. I deal with very poor people, very

poor. They come barefooted and in mud. We give them

milk and bread, sometimes meat, cheese, bologna, clothes,

shoes. Sometimes they need wood which I take from old

packing cases. They take that wood and build themselves a

one-room shelter. They line it inside with old newspapers

which I collect and take to them.

"I remelllber a girl with a rotting foot. I took her and

smeared penicillin all around her foot, and in a few days

she was completely cured. Otherwise, she would have

surely lost the foot, maybe her life. Fig politics," he chuck-

led.

-- 48 --

"I use anything and everything that works. I don't have

no axe to grind, nothing to sell. If it works, I use it.

"They bring me all kinds of sick. I massage them, pray

for them. I can find sore places in their spines. I release

that, but it's the Spirit that does the healing.

"My helpers have seen and they believe the Spirit will

help the sick. Believing is the same as praying, you know. I

suspect that faith and confidence, and with the medicine,

we have done things that medical doctors can't do, haven't

done, wouldn't know how to do. MDs are so limited, you

know. They just have one avenue, chemicals and chemical

therapy. There's so much more.

"But all these things, there's no use trying to talk to

our medical friends about this. They think it's out of order,

you know. I don't care about order, or orders. It's doing

the business, it's curing the sick, and I use it. People

who've given up hope elsewhere, they come from all over

the Border, and we fix them up as best we can. If it works,

we use it.

"I like to use the example of Jesus. He didn't use no

religion. He didn't confine himself to creeds and rules. He

just did what had to be done. The more religions we have

the more division there is, and the less religion there is.

"Well, anyway, some people try to do their part in the

pulpit, others in the workaday world. Maybe I can do my

bit in daily life, be an example. It I can be an example to

others, it would surely he nice. It might help others to go

about doing a little more good than they might otherwise

do. Maybe I'm a reminder. Maybe I remind people to do

good, to go about helping each other. I hope so.

"There is still so much to be done. I can't do it all. I

can only do one thing at a time, but I can do just that-one

thing at a time.

Jesus spent more of His life helping the poor, those

who needed curing. Christianity means helping yonr

brother, if he needs it. From my reading of the Bible it

seems that accepting the Lord as your Savior is the most

-- 49 --

important, but we also need to help those about us who

need help.

"I have found, I honestly believe, that the only thing

you can take with you when you leave this earth is the good

you have done here, the effort you have put out to make it

better when you leave than it was when you came here

that's the only thing you will go away with, the good you

have done."

I sat there, stunned by this old man's simple logic I

looked around the room and I saw hanging on the wall,

among other forms of assorted junk, a medal from Freedom

Foundation "For his aid to Mexican indigents."

Next to that I saw a scroll which the Harlingen Kiwanis

Club had officially selected Ferree as the good Samaritan of

South Texas, claiming that "without personal funds, but

with a big heart and a burning desire to help, he has

worked tirelessly in providing a minimum of food, clothing,

and medical care to these unfortunate peoples "

Even the U.S. Federal government officially recognized

Ferree's efforts, and used to send him, when it had such

surpluses, carloads of foods and farm products to be distrib-

uted among the incredibly poor and destitute along the

Border.

I remembered other things I had picked up concerning

this old man's good work.

At a meeting on hurricane relief in Brownsville, Texas,

John Holland, regional chief of the U.S. Immigration and

Naturalization Service, told members that the Volunteer

Border Relief which Frank Ferree founded and managed,

had done more for good relations between Mexico and

Texas than all other sources--official, unofficial, and

private--put together.

A South Texas businessman said at Rotary luncheon

that Ferree had distributed a million loaves of bread since

he had begun to keep track.

In Honduras, Dr Stephen Youngberg, M.D., who has

done wonders for the destitute of that conutry, said, "The

-- 50 --

main reason I came down here was because I had seen

Frank Ferree doing so much on the Mexican border with so

little."

Lyndon Johnson, while still a senator said: "Voluteer

Border Relief is doing a magnificent work on the Border."

Cameron County Judge Oscar Dancey of Brownsville,

wrote that Ferree "is the Albert Schweitzer of the Rio

Grande Valley."

State Department officials in Washington, D.C., have

written "We have watched Ferree and his large Mexico

program do so much with so little help."

A citizen of the U.S., after observing Ferree at work:

"I don't think we will ever forget Frank Ferree and the

completely unselfish nature of the man. We are constantly

associating Frank with what Reader's Digest phrases "the

most unforgettable character I ever met."

-- 51 --

Frank Ferree, 84, Good Samaritan par excellence. He has

nothing is as poor as the thousands he helps. There is

something of Robin Hood in the old man, although nothing

of the fameous character's had qualities. Ferree begs from

the rich to help the desperately poor who suffer from lack of

food, vitamins, medical care along both sides of the Texas-

Mexican border. Absolutely everything that is given to Fer-

ree, he turns over to the poor, keeping only a scrap of

bread, the bare neeessities of life, for himself: Behind his

simple lifestyle and ways are the elear workings of a mind

sharply honed to get whatever is necessary for his poor

people.

( 52 )

Frank Ferree, 84, Good Samaritan par excellence. He has

nothing is as poor as the thousands he helps. There is

something of Robin Hood in the old man, although nothing

of the fameous character's had qualities. Ferree begs from

the rich to help the desperately poor who suffer from lack of

food, vitamins, medical care along both sides of the Texas-

Mexican border. Absolutely everything that is given to Fer-

ree, he turns over to the poor, keeping only a scrap of

bread, the bare neeessities of life, for himself: Behind his

simple lifestyle and ways are the elear workings of a mind

sharply honed to get whatever is necessary for his poor

people.

( 52 )

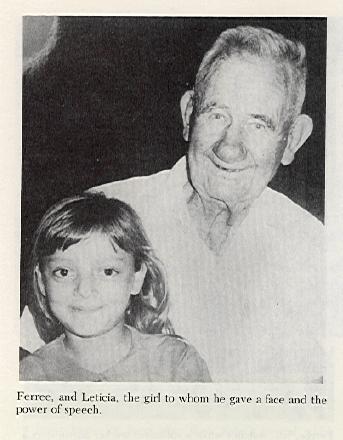

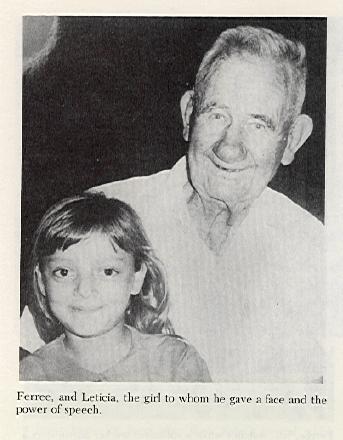

Feree, and Leticia, the girl to whom he gave a face and the

power of speech.

Feree, and Leticia, the girl to whom he gave a face and the

power of speech.

( 53 )

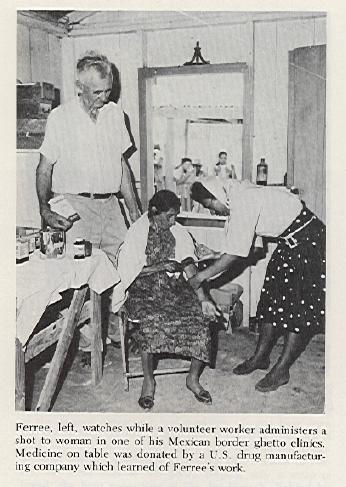

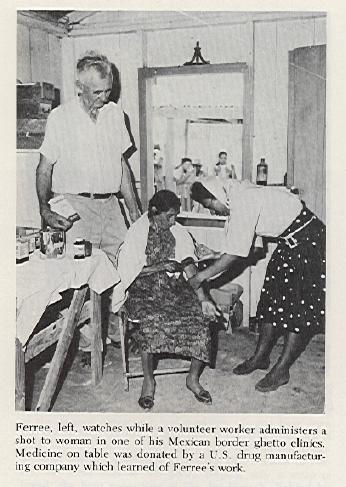

Ferree, left, watches while a volunteer worker administers a

shot to a woman in one of his Mexican border ghetto clinics.

Medicine on table was donated by a U.S. drug manugactur-

ing company which learned of Ferree's work.

( 54 )

Ferree, left, watches while a volunteer worker administers a

shot to a woman in one of his Mexican border ghetto clinics.

Medicine on table was donated by a U.S. drug manugactur-

ing company which learned of Ferree's work.

( 54 )

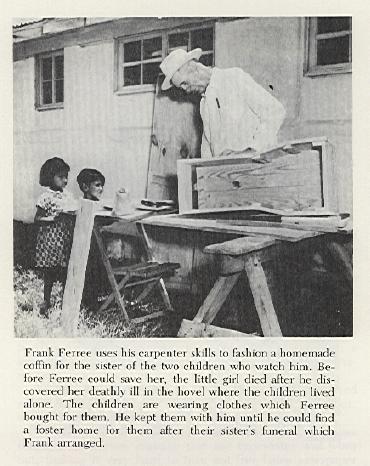

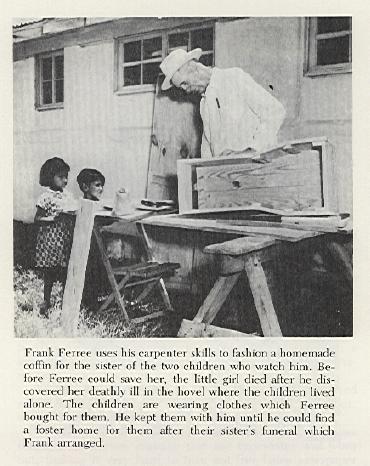

Frank Ferree uses his carpenter skills to fashion a homemade

coffin for the sister of the two children who wateh him. Be-

fore Ferree could save her, the little girl died after he dis-

covered her deathly ill in the hovel where the children lived

alone. The children are wearing clothes which Ferree

bought for them. He kept them with him until he could find

a foster home for them atter their sister's funeral which

Frank arranged.

( 55 )

Frank Ferree uses his carpenter skills to fashion a homemade

coffin for the sister of the two children who wateh him. Be-

fore Ferree could save her, the little girl died after he dis-

covered her deathly ill in the hovel where the children lived

alone. The children are wearing clothes which Ferree

bought for them. He kept them with him until he could find

a foster home for them atter their sister's funeral which

Frank arranged.

( 55 )

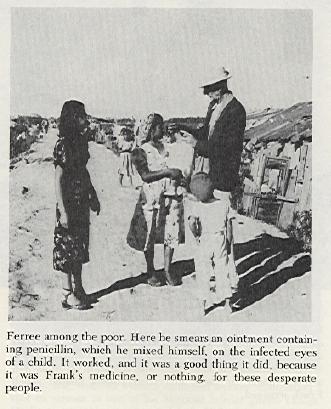

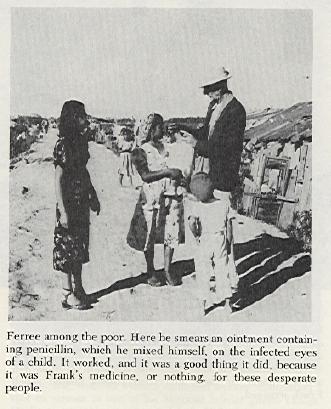

Ferree among the poor. Here he smears an ointment contain-

ing penicillin, which he mixed himself, on the infected eyes

of a child. It worked, and it was a good thing it did, because

it was Frank's medicine, or nothing, for these desperate

people.

( 56 )

Chapter XIII

An Unnoticed Monument to One Man's Human

Kindness

Harlingen, Texas, where Frank lives, has a population of

50,000, of which 40,000 are Mexican-American. It is at the

center of the Rio Grande Valley. It likes to call itself the

hub city of the Valley. Some ten miles from the Border, as

the crow flies, its economy lies deeply rooted in the sur-

rounding agriculture.

Go north on 7th Street, past Andy's Model Market,

across the 77 Sunshine Strip by-pass. On the east are the

practice fields of Harlingen High School. On the west, a

few low-income houses soon give way to three ultra-

modern, magnificent churches of different denominations.

A half mile farther north, on the west side of the paved

road, is Frank Ferree's shack, the poorest of the poor,

where unscheduled helpfulness is the order of the day.

I have seen his response to the needy. Once, in leaner

times, I mentioned casually that my typewriter was worn

out, making it very hard to turn out free-lance newspaper

articles.

To my great surprise and astonishment, a day later one

of Frank's helpers delivered an ancient, but perfectly usable

typewriter. It seems that years ago when one ol the local

railroad freight offices restocked with new typewriters,

-- 57 --

Frank had taken the old typewriters off their hands and

stored them away in his shack, waiting for someone to need

one.

Across the highway and east of Frank's shack lies open

crop land. The Harlingen airport, formerly Harlingen Air

Force Base, is located a couple ot miles away.

The tall brown grass sways in the Gulf breezes around

Frank's house. A dozen salt-cedar trees provide shade, their

sharp, needle-like leaves sighing constantly in the wind. It

sounds as if the souls of all the world's needy and desperate

are collected in the air around Frank's dwelling, crying out

their sadness, their frustrations their hopelessness.

To the south and across the dirt road can be seen the

bare shacks ot the poor. Thev were built on lots provided

from some of Frank's original twenty-three acres.

Just north of his shack are the remains of the old mas-

sage studio which he now uses for storage. In front of this

stands a large concrete monument and plaque facing the

highway. A few citizens of the Valley recently erected this

monument and placed a floodlight to shine On it at night.

The insciption on the monument reads:

"Inasmuch as you have done it to the least of these

my brethren, you have done it to me." Matt. 25:40.

"Headquarters site for Volunteer Border Relief. 1943.

Incorporated to extend free and voluntary aid to the home-

less, the hungry and ill Border residents who care."

Few passers-by even see the monument. Fewer stop to

see what it says. Fewer than that understand what it really

says.

Do-gooders seldom produce revenue. They seldom can

be exploited by commercial interests. There's simply no

monetary profit to the commullity, to the con-artists and

wheeler-dealers.

So an old man does good. Fine, but what's in it for

me? Where's the money angle? Now, you take a tourist-

trap a carnival ride, a sideshow, these you can promote,

these you can exploit, take the suckers to the cleaners, strip

-- 58 --

them of all they've got. But a harmless old man who goes

about doing good?

Several bodies of worn-out trucks rust in the yard.

Scraps of packing cases, cardboard hoxes pressed flat and

stacked neatly, are in front of the house, ready to be loaded

on the truck to be hauled to those who can build shelters

from them.

A large and ancient food refrigerator stands beside the

front door. Here Ferree stores soup bones and interior

meat cuts that can't be sold. Nothing is wasted.

An outside phone rests beneath a crude home-made

box covering to protect it from the elements. The porch is

crumbling. The front door has been off its hinges for years,

long gone to "someone who needed it" more than he. A

hole in the floor is now covered with a piece of plywood,

since one of Frank's visitors fell through it.

He's cleaned up the place somewhat from the utter

chaos of refuse and stored material that it used to be.

In the front room there are boxes of grapes, wilted

fruit, and vegetables which he begged from storekeepers in

town late today. He'll sort out the rotten and unusable,

throw out the questionable meat to the dozen stray cats and

half dozen dogs that hang around.

The next room has a cot where Frank sleeps. On the

north side of the room is an assortment of nonperishable

things which he has repaired and stored until someone

needs them. Mended, patched blankets, old quilts, end

rolls of newsprint, worn-out typewriters, old desks chairs,

tools, scraps and bits that someday, somewhere, will be just

the thing to ease a desperate man over a crisis, make his

life more bearable for a while, give him hope and love and

the knowledge that someone cares for his fate.

Along the north side of the house, fairly well closed off

from the rest, is what Frank has fixed up into a combination

storage room and dormitory.

Anyone, man, woman, or child, who has no place to

spend the night is welcome to sleep there. Sometimes or-

-- 59 --

phans, their parents dead, or runaways have spent weeks

there until Frank can find relatives who will accept them

until he can place them with someone else.

Frank's "people" are the world's mistakes, those who

have reached the absolute bottom. Many are so far gone, so

humble, so poor, such human wrecks, that no reputable

church, government agency, or private citizen will have

anything to do with them.

But Frank turns nobody away. All have a place to

sleep, and a bite to eat at his house. All will be treated as

dignified human beings. All get a boost of self-esteem from

this most humble of men.

Perhaps the most interesting room of this shack is the

back roon. Here in little more than a ten by twelve foot

square, Frank has combined a library, workroom, kitchen,

visiting area, bathroom, and anything else that might be

needed.

A rusty barrel, placed upright, is on the north side of

the room. A stove pipe leads straight up throtlgh the roof, a

light bulb on a single electrical cord comes straight down

from the roof.

Next to the barrel is a rough table, usually covered by

a tablecloth made out of paper torn off the end rolls from

the local daily's presses. A cabinet on the wall holds his "li-

brary." a few books, the Bible, and tons of clippings about

himself and those things he's interested in--the plight of

the poor, the injustices of the world, the things he's read

about and thinks he can do something about.

A telephone is next to the door. A twelve-inch hole in

the floor serves him well when he bathes out of a tub, or

just washes his feet or face. The water drains through the

hole.

An ancient kitchen cupboard holds very little of any

edibles. It is stocked mostly with medical tapes, rolls of

bandages, vitamins, pills, pastes. and powders to he used

on the desperate, forgotten people down by the river.

Here in his kitchen, Frank spends most of his inside

-- 60 --

hours before retiring at night, a crust ot toast on the bar-

rel, the Bible to read, medicines to prepare, phone calls to

make, plans to write down, schedules to follow, now and

then an important letter to someone who can help.

Here he holds conferences with those who wish to con-

fer.

Overhead and out back the night winds sigh through

the sharp leaves ot the salt cedars, and the tall brown

grasses rustle with the air.

He is a lonely man. His work is his all. He has little

time to socialize. Few are those who come to pass the time

of day with him, to enjoy his company. He is an original

man in every sense of the word, a true noncomformist

without being obnoxious about it. His is the exciting

movement of a brilliant mind, well-versed in worldly wis-

dom discarding the dross, the chaff; the unusable, clinging

doggedly to that which works, that which is eternally true,

that which gets to the heart of the matter and brings de-

sired results.

Christmas Day, New Year's Day, Thanksgiving Day,

he is usually alone; minding his business, attending to odd

chores, reading, playing with his cats and dogs

Twice in recent years I took him a bottle of cheap

wine. Once I included a Christmas cake, warning him

sternly to eat it himself; and not give it to the poor. I've

never seen him drink, but I trust he rememers the Bible

reference to a little wine being good for the stomach.

At one time he had a stray dog of which he became

particularly fond It seems a neighbor boy could not keep

his puppy at home, and the pup wound up at Frank's door

where it found food and love.

One of Frank's friends, Eleanor Galt, a newspaper

photographer, had especially developed a love for the dog

after she'd seen how close Frank and the dog had grown

When the pup was taken to the vet for his shots, the vet

demanded he be given a name. Gale Armstrong, Franks

helper, thinking of the photographer's love for the dog, said

-- 61 --

"All right. Call it Eleanor." Later Armstrong found out the

dog was a male, but it was too late to change the records

then.

For the next six months Eleanor was a faithful, loyal

helper to Frank, seeming to take a personal interest in

guarding his master's shack and greeting visitors with affec-

tion.

"He used to sleep outside the shack, just under the

window where I slept." Frank said.

Then Eleanor was hit by a car, and for four days he

didn't show up. On the morning of the fourth day, Frank,

beside himself with loneliness, got down on his knees in

the gravel beside his truck and asked God to protect

Eleanor and bring him back.

A few hours later a neighhor woman saw the dog trying

to crawl back to Frank's house.

That night Frank gave the injured dog leftover ham-

burger meat and a bowl of water. At bedtime, the dog

moved painfully to a spot beneath the window and close to

the master he loved.

Early the next morning Armstrong placed the dog in

the truck, and with Frank, took off for an animal hospital.

There they found out the dog had his back broken in two

places.

Frank, with tears in his eyes, gave permission to have

Eleanor put to sleep forever.

A tremendous, uncanny love had grown up between

the lonely old man and the pup that had wandered in off

the street to be his friend.

I guess Eleanor sensed his life with me would be

short," Frank said. "Perhaps, I think, I have a feeling that

his spirit will remain here at his adopted home, guarding

the place like he always did."

A few weeks later, Frank received another dog, similar

in appearance to Eleanor "I named him Eleanor II," he

said. "I believe it is Eleanor's spirit come back in this new

dog. He's got the same movements, same favorite hideout.

-- 62 --

Same way of stealing food and eating it. Same way of com-

ing when I call him. Even sleeps under the window by my

cot.

"Do you believe in reincarnation, then? Do you be-

lieve that people's spirits come back again in different

bodies" I asked. I really wanted to know what his agile

mind thought about the possibility.

'Can't say about that," he said, smiling. 'But I believe

that in this case, the spirit of Eleanor came back to guard

the house and lives in Eleanor II. Of that, I'm convinced."

Nowadays Mrs. Gerarda Lopez de Leon and her chil-

dren help Frank with the physical labor ot sorting tood and

supplies and loading them on his trucks.

Mrs. Lopez arrived in Matamoros several years ago,

sick, and with her small children. She had no money. All

her belongings were tied up in an old sheet which she car-

ried in one hand. Opening the sheet, she tied its corners to

branches of a mesquite tree and there made her home. She

lay in the shade by day, semi-conscious with fever, while

her small children played nearby.

Some people brought her food from Ferree's clinic.

One day Frank visited her. Immediately on seeing her con-

dition, he loaded her into his truck and took her to the doc-

tor. By this time she was so far gone that she barely re-

sponded. She was given injections and sent home.

Several times Ferree visited her at her makeshift house

beneath the sheet. Finally, seeing she was not improving,

he brought her across to a doctor in Harlingen. Again

medicines failed to cure her. For five months, she lan-

guished. Ferree sensed that the big trouble was that she'd

lost all hope. Alone and sick and with children, she could

see no way out.

Ferree decided to give her a purpose a goal. He sim-

ply told her to get well so she could help him with his

work. He needed her help.

That was years ago.

-- 63 --

"Now." she says, "I live only to help this kind old man

in old age. Only when I help him, do I feel OK I want

to work for him, to clean his house, to make him comfort-

able, to ease his life. I've seen him help thousands of others

who had no home, no food, no friends. I want to help such

a fine man in such fine work."

True to the experiences of many saints of the past of

which Frank Ferree never heard, he began to see and un-

derstand things which are denied to ordinary mortals

For example, on his lonely rounds through the dusty

brush country in the back ways, the forgotten ways along

the Texas-Mexican border he would look out of his truck

cab over the vast nothingness, and it would all seem so

beautiful to him, so fitting, so complete and he never

doubted for an instant that it was all formed and under the

intense and loving and constant care of an All-loving

Father. He was convinced of this, beyond theory, beyond

argument, beyond doubt. It just simply was so he knew

The short mesquite trees, the thorns the low brush,

the arid soil, the strong Gulf winds, the semi-tropical suns,

the endless days, the years he had lived in the flat land

along the muddy Rio Grande, the cool nights the soft

breeses, the close starlit sky, even the tall, stately palms,

all seemed a part of him. He was one with mankind with

Creation.

Such experiences down through the ages have heen

called Illumination, Cosmic Consciousness, Divine Revela-

tion. and they have been the supreme goal of philosophers,

mystics, thinkers, ever since recorded history only a very

select few of the pure, the honest, the ones capable of

deepest love, have ever been blessed thusly.

Frank never heard of such speculations. He knows only

that he feels an attunement with God, sparingly at first, but

now more and more.

-- 64 --

Ferree among the poor. Here he smears an ointment contain-

ing penicillin, which he mixed himself, on the infected eyes

of a child. It worked, and it was a good thing it did, because

it was Frank's medicine, or nothing, for these desperate

people.

( 56 )

Chapter XIII

An Unnoticed Monument to One Man's Human

Kindness

Harlingen, Texas, where Frank lives, has a population of

50,000, of which 40,000 are Mexican-American. It is at the

center of the Rio Grande Valley. It likes to call itself the

hub city of the Valley. Some ten miles from the Border, as

the crow flies, its economy lies deeply rooted in the sur-

rounding agriculture.

Go north on 7th Street, past Andy's Model Market,

across the 77 Sunshine Strip by-pass. On the east are the

practice fields of Harlingen High School. On the west, a

few low-income houses soon give way to three ultra-

modern, magnificent churches of different denominations.

A half mile farther north, on the west side of the paved

road, is Frank Ferree's shack, the poorest of the poor,

where unscheduled helpfulness is the order of the day.

I have seen his response to the needy. Once, in leaner

times, I mentioned casually that my typewriter was worn

out, making it very hard to turn out free-lance newspaper

articles.

To my great surprise and astonishment, a day later one

of Frank's helpers delivered an ancient, but perfectly usable

typewriter. It seems that years ago when one ol the local

railroad freight offices restocked with new typewriters,

-- 57 --

Frank had taken the old typewriters off their hands and

stored them away in his shack, waiting for someone to need

one.

Across the highway and east of Frank's shack lies open

crop land. The Harlingen airport, formerly Harlingen Air

Force Base, is located a couple ot miles away.

The tall brown grass sways in the Gulf breezes around

Frank's house. A dozen salt-cedar trees provide shade, their

sharp, needle-like leaves sighing constantly in the wind. It

sounds as if the souls of all the world's needy and desperate

are collected in the air around Frank's dwelling, crying out

their sadness, their frustrations their hopelessness.

To the south and across the dirt road can be seen the

bare shacks ot the poor. Thev were built on lots provided

from some of Frank's original twenty-three acres.

Just north of his shack are the remains of the old mas-

sage studio which he now uses for storage. In front of this

stands a large concrete monument and plaque facing the

highway. A few citizens of the Valley recently erected this

monument and placed a floodlight to shine On it at night.

The insciption on the monument reads:

"Inasmuch as you have done it to the least of these

my brethren, you have done it to me." Matt. 25:40.

"Headquarters site for Volunteer Border Relief. 1943.

Incorporated to extend free and voluntary aid to the home-

less, the hungry and ill Border residents who care."

Few passers-by even see the monument. Fewer stop to

see what it says. Fewer than that understand what it really

says.

Do-gooders seldom produce revenue. They seldom can

be exploited by commercial interests. There's simply no

monetary profit to the commullity, to the con-artists and

wheeler-dealers.

So an old man does good. Fine, but what's in it for

me? Where's the money angle? Now, you take a tourist-

trap a carnival ride, a sideshow, these you can promote,

these you can exploit, take the suckers to the cleaners, strip

-- 58 --

them of all they've got. But a harmless old man who goes

about doing good?

Several bodies of worn-out trucks rust in the yard.

Scraps of packing cases, cardboard hoxes pressed flat and

stacked neatly, are in front of the house, ready to be loaded

on the truck to be hauled to those who can build shelters

from them.

A large and ancient food refrigerator stands beside the

front door. Here Ferree stores soup bones and interior

meat cuts that can't be sold. Nothing is wasted.

An outside phone rests beneath a crude home-made

box covering to protect it from the elements. The porch is

crumbling. The front door has been off its hinges for years,

long gone to "someone who needed it" more than he. A

hole in the floor is now covered with a piece of plywood,

since one of Frank's visitors fell through it.

He's cleaned up the place somewhat from the utter

chaos of refuse and stored material that it used to be.

In the front room there are boxes of grapes, wilted

fruit, and vegetables which he begged from storekeepers in

town late today. He'll sort out the rotten and unusable,

throw out the questionable meat to the dozen stray cats and

half dozen dogs that hang around.

The next room has a cot where Frank sleeps. On the

north side of the room is an assortment of nonperishable

things which he has repaired and stored until someone

needs them. Mended, patched blankets, old quilts, end

rolls of newsprint, worn-out typewriters, old desks chairs,

tools, scraps and bits that someday, somewhere, will be just

the thing to ease a desperate man over a crisis, make his

life more bearable for a while, give him hope and love and

the knowledge that someone cares for his fate.

Along the north side of the house, fairly well closed off

from the rest, is what Frank has fixed up into a combination

storage room and dormitory.

Anyone, man, woman, or child, who has no place to

spend the night is welcome to sleep there. Sometimes or-

-- 59 --

phans, their parents dead, or runaways have spent weeks

there until Frank can find relatives who will accept them

until he can place them with someone else.

Frank's "people" are the world's mistakes, those who

have reached the absolute bottom. Many are so far gone, so

humble, so poor, such human wrecks, that no reputable

church, government agency, or private citizen will have

anything to do with them.

But Frank turns nobody away. All have a place to

sleep, and a bite to eat at his house. All will be treated as

dignified human beings. All get a boost of self-esteem from

this most humble of men.

Perhaps the most interesting room of this shack is the

back roon. Here in little more than a ten by twelve foot

square, Frank has combined a library, workroom, kitchen,

visiting area, bathroom, and anything else that might be

needed.

A rusty barrel, placed upright, is on the north side of

the room. A stove pipe leads straight up throtlgh the roof, a

light bulb on a single electrical cord comes straight down

from the roof.

Next to the barrel is a rough table, usually covered by

a tablecloth made out of paper torn off the end rolls from

the local daily's presses. A cabinet on the wall holds his "li-

brary." a few books, the Bible, and tons of clippings about

himself and those things he's interested in--the plight of

the poor, the injustices of the world, the things he's read

about and thinks he can do something about.

A telephone is next to the door. A twelve-inch hole in

the floor serves him well when he bathes out of a tub, or

just washes his feet or face. The water drains through the

hole.

An ancient kitchen cupboard holds very little of any

edibles. It is stocked mostly with medical tapes, rolls of

bandages, vitamins, pills, pastes. and powders to he used

on the desperate, forgotten people down by the river.

Here in his kitchen, Frank spends most of his inside

-- 60 --

hours before retiring at night, a crust ot toast on the bar-

rel, the Bible to read, medicines to prepare, phone calls to

make, plans to write down, schedules to follow, now and

then an important letter to someone who can help.

Here he holds conferences with those who wish to con-

fer.

Overhead and out back the night winds sigh through

the sharp leaves ot the salt cedars, and the tall brown

grasses rustle with the air.

He is a lonely man. His work is his all. He has little

time to socialize. Few are those who come to pass the time

of day with him, to enjoy his company. He is an original

man in every sense of the word, a true noncomformist

without being obnoxious about it. His is the exciting

movement of a brilliant mind, well-versed in worldly wis-

dom discarding the dross, the chaff; the unusable, clinging

doggedly to that which works, that which is eternally true,

that which gets to the heart of the matter and brings de-

sired results.

Christmas Day, New Year's Day, Thanksgiving Day,

he is usually alone; minding his business, attending to odd

chores, reading, playing with his cats and dogs

Twice in recent years I took him a bottle of cheap

wine. Once I included a Christmas cake, warning him

sternly to eat it himself; and not give it to the poor. I've

never seen him drink, but I trust he rememers the Bible

reference to a little wine being good for the stomach.

At one time he had a stray dog of which he became

particularly fond It seems a neighbor boy could not keep

his puppy at home, and the pup wound up at Frank's door

where it found food and love.

One of Frank's friends, Eleanor Galt, a newspaper

photographer, had especially developed a love for the dog

after she'd seen how close Frank and the dog had grown

When the pup was taken to the vet for his shots, the vet

demanded he be given a name. Gale Armstrong, Franks

helper, thinking of the photographer's love for the dog, said

-- 61 --

"All right. Call it Eleanor." Later Armstrong found out the

dog was a male, but it was too late to change the records

then.

For the next six months Eleanor was a faithful, loyal

helper to Frank, seeming to take a personal interest in

guarding his master's shack and greeting visitors with affec-

tion.

"He used to sleep outside the shack, just under the

window where I slept." Frank said.

Then Eleanor was hit by a car, and for four days he

didn't show up. On the morning of the fourth day, Frank,

beside himself with loneliness, got down on his knees in

the gravel beside his truck and asked God to protect

Eleanor and bring him back.

A few hours later a neighhor woman saw the dog trying

to crawl back to Frank's house.

That night Frank gave the injured dog leftover ham-

burger meat and a bowl of water. At bedtime, the dog

moved painfully to a spot beneath the window and close to

the master he loved.

Early the next morning Armstrong placed the dog in

the truck, and with Frank, took off for an animal hospital.

There they found out the dog had his back broken in two

places.

Frank, with tears in his eyes, gave permission to have

Eleanor put to sleep forever.

A tremendous, uncanny love had grown up between

the lonely old man and the pup that had wandered in off

the street to be his friend.

I guess Eleanor sensed his life with me would be

short," Frank said. "Perhaps, I think, I have a feeling that

his spirit will remain here at his adopted home, guarding

the place like he always did."

A few weeks later, Frank received another dog, similar

in appearance to Eleanor "I named him Eleanor II," he

said. "I believe it is Eleanor's spirit come back in this new

dog. He's got the same movements, same favorite hideout.

-- 62 --

Same way of stealing food and eating it. Same way of com-

ing when I call him. Even sleeps under the window by my

cot.

"Do you believe in reincarnation, then? Do you be-

lieve that people's spirits come back again in different

bodies" I asked. I really wanted to know what his agile

mind thought about the possibility.

'Can't say about that," he said, smiling. 'But I believe

that in this case, the spirit of Eleanor came back to guard

the house and lives in Eleanor II. Of that, I'm convinced."

Nowadays Mrs. Gerarda Lopez de Leon and her chil-

dren help Frank with the physical labor ot sorting tood and

supplies and loading them on his trucks.

Mrs. Lopez arrived in Matamoros several years ago,

sick, and with her small children. She had no money. All

her belongings were tied up in an old sheet which she car-

ried in one hand. Opening the sheet, she tied its corners to

branches of a mesquite tree and there made her home. She

lay in the shade by day, semi-conscious with fever, while

her small children played nearby.

Some people brought her food from Ferree's clinic.

One day Frank visited her. Immediately on seeing her con-

dition, he loaded her into his truck and took her to the doc-

tor. By this time she was so far gone that she barely re-

sponded. She was given injections and sent home.

Several times Ferree visited her at her makeshift house

beneath the sheet. Finally, seeing she was not improving,

he brought her across to a doctor in Harlingen. Again

medicines failed to cure her. For five months, she lan-

guished. Ferree sensed that the big trouble was that she'd

lost all hope. Alone and sick and with children, she could

see no way out.

Ferree decided to give her a purpose a goal. He sim-

ply told her to get well so she could help him with his

work. He needed her help.

That was years ago.

-- 63 --

"Now." she says, "I live only to help this kind old man

in old age. Only when I help him, do I feel OK I want

to work for him, to clean his house, to make him comfort-

able, to ease his life. I've seen him help thousands of others

who had no home, no food, no friends. I want to help such

a fine man in such fine work."

True to the experiences of many saints of the past of

which Frank Ferree never heard, he began to see and un-

derstand things which are denied to ordinary mortals

For example, on his lonely rounds through the dusty

brush country in the back ways, the forgotten ways along

the Texas-Mexican border he would look out of his truck

cab over the vast nothingness, and it would all seem so

beautiful to him, so fitting, so complete and he never

doubted for an instant that it was all formed and under the

intense and loving and constant care of an All-loving

Father. He was convinced of this, beyond theory, beyond

argument, beyond doubt. It just simply was so he knew

The short mesquite trees, the thorns the low brush,

the arid soil, the strong Gulf winds, the semi-tropical suns,

the endless days, the years he had lived in the flat land

along the muddy Rio Grande, the cool nights the soft

breeses, the close starlit sky, even the tall, stately palms,

all seemed a part of him. He was one with mankind with

Creation.

Such experiences down through the ages have heen

called Illumination, Cosmic Consciousness, Divine Revela-

tion. and they have been the supreme goal of philosophers,

mystics, thinkers, ever since recorded history only a very

select few of the pure, the honest, the ones capable of

deepest love, have ever been blessed thusly.

Frank never heard of such speculations. He knows only

that he feels an attunement with God, sparingly at first, but

now more and more.

-- 64 --

to next chapter

Return to Border Angel table of contents.

Frank Ferree, 84, Good Samaritan par excellence. He has

nothing is as poor as the thousands he helps. There is

something of Robin Hood in the old man, although nothing

of the fameous character's had qualities. Ferree begs from

the rich to help the desperately poor who suffer from lack of

food, vitamins, medical care along both sides of the Texas-

Mexican border. Absolutely everything that is given to Fer-

ree, he turns over to the poor, keeping only a scrap of

bread, the bare neeessities of life, for himself: Behind his

simple lifestyle and ways are the elear workings of a mind

sharply honed to get whatever is necessary for his poor

people.

( 52 )

Frank Ferree, 84, Good Samaritan par excellence. He has

nothing is as poor as the thousands he helps. There is

something of Robin Hood in the old man, although nothing

of the fameous character's had qualities. Ferree begs from

the rich to help the desperately poor who suffer from lack of

food, vitamins, medical care along both sides of the Texas-

Mexican border. Absolutely everything that is given to Fer-

ree, he turns over to the poor, keeping only a scrap of

bread, the bare neeessities of life, for himself: Behind his

simple lifestyle and ways are the elear workings of a mind

sharply honed to get whatever is necessary for his poor

people.

( 52 )

Feree, and Leticia, the girl to whom he gave a face and the

power of speech.

Feree, and Leticia, the girl to whom he gave a face and the

power of speech.

Ferree, left, watches while a volunteer worker administers a

shot to a woman in one of his Mexican border ghetto clinics.

Medicine on table was donated by a U.S. drug manugactur-

ing company which learned of Ferree's work.

( 54 )

Ferree, left, watches while a volunteer worker administers a

shot to a woman in one of his Mexican border ghetto clinics.

Medicine on table was donated by a U.S. drug manugactur-

ing company which learned of Ferree's work.

( 54 )

Frank Ferree uses his carpenter skills to fashion a homemade

coffin for the sister of the two children who wateh him. Be-

fore Ferree could save her, the little girl died after he dis-

covered her deathly ill in the hovel where the children lived

alone. The children are wearing clothes which Ferree

bought for them. He kept them with him until he could find

a foster home for them atter their sister's funeral which

Frank arranged.

( 55 )

Frank Ferree uses his carpenter skills to fashion a homemade

coffin for the sister of the two children who wateh him. Be-

fore Ferree could save her, the little girl died after he dis-

covered her deathly ill in the hovel where the children lived

alone. The children are wearing clothes which Ferree

bought for them. He kept them with him until he could find

a foster home for them atter their sister's funeral which

Frank arranged.

( 55 )

Ferree among the poor. Here he smears an ointment contain-

ing penicillin, which he mixed himself, on the infected eyes

of a child. It worked, and it was a good thing it did, because

it was Frank's medicine, or nothing, for these desperate

people.

( 56 )

Chapter XIII

An Unnoticed Monument to One Man's Human

Kindness

Harlingen, Texas, where Frank lives, has a population of

50,000, of which 40,000 are Mexican-American. It is at the

center of the Rio Grande Valley. It likes to call itself the

hub city of the Valley. Some ten miles from the Border, as

the crow flies, its economy lies deeply rooted in the sur-

rounding agriculture.

Go north on 7th Street, past Andy's Model Market,

across the 77 Sunshine Strip by-pass. On the east are the

practice fields of Harlingen High School. On the west, a

few low-income houses soon give way to three ultra-

modern, magnificent churches of different denominations.

A half mile farther north, on the west side of the paved

road, is Frank Ferree's shack, the poorest of the poor,

where unscheduled helpfulness is the order of the day.

I have seen his response to the needy. Once, in leaner

times, I mentioned casually that my typewriter was worn

out, making it very hard to turn out free-lance newspaper

articles.

To my great surprise and astonishment, a day later one

of Frank's helpers delivered an ancient, but perfectly usable

typewriter. It seems that years ago when one ol the local

railroad freight offices restocked with new typewriters,

-- 57 --

Frank had taken the old typewriters off their hands and

stored them away in his shack, waiting for someone to need

one.

Across the highway and east of Frank's shack lies open

crop land. The Harlingen airport, formerly Harlingen Air

Force Base, is located a couple ot miles away.

The tall brown grass sways in the Gulf breezes around

Frank's house. A dozen salt-cedar trees provide shade, their

sharp, needle-like leaves sighing constantly in the wind. It

sounds as if the souls of all the world's needy and desperate

are collected in the air around Frank's dwelling, crying out

their sadness, their frustrations their hopelessness.

To the south and across the dirt road can be seen the

bare shacks ot the poor. Thev were built on lots provided

from some of Frank's original twenty-three acres.

Just north of his shack are the remains of the old mas-

sage studio which he now uses for storage. In front of this

stands a large concrete monument and plaque facing the

highway. A few citizens of the Valley recently erected this

monument and placed a floodlight to shine On it at night.

The insciption on the monument reads:

"Inasmuch as you have done it to the least of these

my brethren, you have done it to me." Matt. 25:40.

"Headquarters site for Volunteer Border Relief. 1943.

Incorporated to extend free and voluntary aid to the home-

less, the hungry and ill Border residents who care."

Few passers-by even see the monument. Fewer stop to

see what it says. Fewer than that understand what it really

says.

Do-gooders seldom produce revenue. They seldom can

be exploited by commercial interests. There's simply no

monetary profit to the commullity, to the con-artists and

wheeler-dealers.

So an old man does good. Fine, but what's in it for

me? Where's the money angle? Now, you take a tourist-

trap a carnival ride, a sideshow, these you can promote,

these you can exploit, take the suckers to the cleaners, strip

-- 58 --

them of all they've got. But a harmless old man who goes

about doing good?

Several bodies of worn-out trucks rust in the yard.

Scraps of packing cases, cardboard hoxes pressed flat and

stacked neatly, are in front of the house, ready to be loaded

on the truck to be hauled to those who can build shelters

from them.

A large and ancient food refrigerator stands beside the

front door. Here Ferree stores soup bones and interior

meat cuts that can't be sold. Nothing is wasted.

An outside phone rests beneath a crude home-made

box covering to protect it from the elements. The porch is

crumbling. The front door has been off its hinges for years,

long gone to "someone who needed it" more than he. A

hole in the floor is now covered with a piece of plywood,

since one of Frank's visitors fell through it.

He's cleaned up the place somewhat from the utter

chaos of refuse and stored material that it used to be.

In the front room there are boxes of grapes, wilted

fruit, and vegetables which he begged from storekeepers in

town late today. He'll sort out the rotten and unusable,

throw out the questionable meat to the dozen stray cats and

half dozen dogs that hang around.

The next room has a cot where Frank sleeps. On the

north side of the room is an assortment of nonperishable

things which he has repaired and stored until someone

needs them. Mended, patched blankets, old quilts, end

rolls of newsprint, worn-out typewriters, old desks chairs,

tools, scraps and bits that someday, somewhere, will be just

the thing to ease a desperate man over a crisis, make his

life more bearable for a while, give him hope and love and

the knowledge that someone cares for his fate.

Along the north side of the house, fairly well closed off

from the rest, is what Frank has fixed up into a combination

storage room and dormitory.

Anyone, man, woman, or child, who has no place to

spend the night is welcome to sleep there. Sometimes or-

-- 59 --

phans, their parents dead, or runaways have spent weeks

there until Frank can find relatives who will accept them

until he can place them with someone else.

Frank's "people" are the world's mistakes, those who

have reached the absolute bottom. Many are so far gone, so

humble, so poor, such human wrecks, that no reputable

church, government agency, or private citizen will have

anything to do with them.

But Frank turns nobody away. All have a place to

sleep, and a bite to eat at his house. All will be treated as

dignified human beings. All get a boost of self-esteem from

this most humble of men.

Perhaps the most interesting room of this shack is the

back roon. Here in little more than a ten by twelve foot

square, Frank has combined a library, workroom, kitchen,

visiting area, bathroom, and anything else that might be

needed.

A rusty barrel, placed upright, is on the north side of

the room. A stove pipe leads straight up throtlgh the roof, a

light bulb on a single electrical cord comes straight down

from the roof.

Next to the barrel is a rough table, usually covered by

a tablecloth made out of paper torn off the end rolls from

the local daily's presses. A cabinet on the wall holds his "li-

brary." a few books, the Bible, and tons of clippings about

himself and those things he's interested in--the plight of

the poor, the injustices of the world, the things he's read

about and thinks he can do something about.

A telephone is next to the door. A twelve-inch hole in

the floor serves him well when he bathes out of a tub, or

just washes his feet or face. The water drains through the

hole.

An ancient kitchen cupboard holds very little of any

edibles. It is stocked mostly with medical tapes, rolls of

bandages, vitamins, pills, pastes. and powders to he used

on the desperate, forgotten people down by the river.

Here in his kitchen, Frank spends most of his inside

-- 60 --

hours before retiring at night, a crust ot toast on the bar-

rel, the Bible to read, medicines to prepare, phone calls to

make, plans to write down, schedules to follow, now and

then an important letter to someone who can help.

Here he holds conferences with those who wish to con-

fer.

Overhead and out back the night winds sigh through

the sharp leaves ot the salt cedars, and the tall brown

grasses rustle with the air.

He is a lonely man. His work is his all. He has little

time to socialize. Few are those who come to pass the time

of day with him, to enjoy his company. He is an original

man in every sense of the word, a true noncomformist

without being obnoxious about it. His is the exciting

movement of a brilliant mind, well-versed in worldly wis-

dom discarding the dross, the chaff; the unusable, clinging

doggedly to that which works, that which is eternally true,

that which gets to the heart of the matter and brings de-

sired results.

Christmas Day, New Year's Day, Thanksgiving Day,

he is usually alone; minding his business, attending to odd

chores, reading, playing with his cats and dogs

Twice in recent years I took him a bottle of cheap

wine. Once I included a Christmas cake, warning him

sternly to eat it himself; and not give it to the poor. I've

never seen him drink, but I trust he rememers the Bible

reference to a little wine being good for the stomach.

At one time he had a stray dog of which he became

particularly fond It seems a neighbor boy could not keep

his puppy at home, and the pup wound up at Frank's door

where it found food and love.

One of Frank's friends, Eleanor Galt, a newspaper

photographer, had especially developed a love for the dog

after she'd seen how close Frank and the dog had grown

When the pup was taken to the vet for his shots, the vet

demanded he be given a name. Gale Armstrong, Franks

helper, thinking of the photographer's love for the dog, said

-- 61 --

"All right. Call it Eleanor." Later Armstrong found out the

dog was a male, but it was too late to change the records

then.

For the next six months Eleanor was a faithful, loyal

helper to Frank, seeming to take a personal interest in

guarding his master's shack and greeting visitors with affec-

tion.

"He used to sleep outside the shack, just under the

window where I slept." Frank said.

Then Eleanor was hit by a car, and for four days he

didn't show up. On the morning of the fourth day, Frank,

beside himself with loneliness, got down on his knees in

the gravel beside his truck and asked God to protect

Eleanor and bring him back.

A few hours later a neighhor woman saw the dog trying

to crawl back to Frank's house.

That night Frank gave the injured dog leftover ham-

burger meat and a bowl of water. At bedtime, the dog

moved painfully to a spot beneath the window and close to

the master he loved.

Early the next morning Armstrong placed the dog in

the truck, and with Frank, took off for an animal hospital.

There they found out the dog had his back broken in two

places.

Frank, with tears in his eyes, gave permission to have

Eleanor put to sleep forever.

A tremendous, uncanny love had grown up between

the lonely old man and the pup that had wandered in off

the street to be his friend.

I guess Eleanor sensed his life with me would be

short," Frank said. "Perhaps, I think, I have a feeling that

his spirit will remain here at his adopted home, guarding

the place like he always did."

A few weeks later, Frank received another dog, similar

in appearance to Eleanor "I named him Eleanor II," he

said. "I believe it is Eleanor's spirit come back in this new

dog. He's got the same movements, same favorite hideout.

-- 62 --

Same way of stealing food and eating it. Same way of com-

ing when I call him. Even sleeps under the window by my

cot.

"Do you believe in reincarnation, then? Do you be-

lieve that people's spirits come back again in different

bodies" I asked. I really wanted to know what his agile

mind thought about the possibility.

'Can't say about that," he said, smiling. 'But I believe

that in this case, the spirit of Eleanor came back to guard

the house and lives in Eleanor II. Of that, I'm convinced."

Nowadays Mrs. Gerarda Lopez de Leon and her chil-

dren help Frank with the physical labor ot sorting tood and

supplies and loading them on his trucks.

Mrs. Lopez arrived in Matamoros several years ago,

sick, and with her small children. She had no money. All

her belongings were tied up in an old sheet which she car-

ried in one hand. Opening the sheet, she tied its corners to

branches of a mesquite tree and there made her home. She

lay in the shade by day, semi-conscious with fever, while

her small children played nearby.

Some people brought her food from Ferree's clinic.

One day Frank visited her. Immediately on seeing her con-

dition, he loaded her into his truck and took her to the doc-

tor. By this time she was so far gone that she barely re-

sponded. She was given injections and sent home.

Several times Ferree visited her at her makeshift house

beneath the sheet. Finally, seeing she was not improving,

he brought her across to a doctor in Harlingen. Again

medicines failed to cure her. For five months, she lan-

guished. Ferree sensed that the big trouble was that she'd

lost all hope. Alone and sick and with children, she could

see no way out.

Ferree decided to give her a purpose a goal. He sim-

ply told her to get well so she could help him with his

work. He needed her help.

That was years ago.

-- 63 --

"Now." she says, "I live only to help this kind old man

in old age. Only when I help him, do I feel OK I want

to work for him, to clean his house, to make him comfort-

able, to ease his life. I've seen him help thousands of others

who had no home, no food, no friends. I want to help such

a fine man in such fine work."

True to the experiences of many saints of the past of

which Frank Ferree never heard, he began to see and un-

derstand things which are denied to ordinary mortals

For example, on his lonely rounds through the dusty

brush country in the back ways, the forgotten ways along

the Texas-Mexican border he would look out of his truck

cab over the vast nothingness, and it would all seem so

beautiful to him, so fitting, so complete and he never

doubted for an instant that it was all formed and under the

intense and loving and constant care of an All-loving

Father. He was convinced of this, beyond theory, beyond

argument, beyond doubt. It just simply was so he knew

The short mesquite trees, the thorns the low brush,

the arid soil, the strong Gulf winds, the semi-tropical suns,

the endless days, the years he had lived in the flat land

along the muddy Rio Grande, the cool nights the soft

breeses, the close starlit sky, even the tall, stately palms,

all seemed a part of him. He was one with mankind with

Creation.

Such experiences down through the ages have heen

called Illumination, Cosmic Consciousness, Divine Revela-

tion. and they have been the supreme goal of philosophers,

mystics, thinkers, ever since recorded history only a very

select few of the pure, the honest, the ones capable of

deepest love, have ever been blessed thusly.

Frank never heard of such speculations. He knows only

that he feels an attunement with God, sparingly at first, but

now more and more.

-- 64 --

Ferree among the poor. Here he smears an ointment contain-

ing penicillin, which he mixed himself, on the infected eyes

of a child. It worked, and it was a good thing it did, because

it was Frank's medicine, or nothing, for these desperate

people.

( 56 )

Chapter XIII

An Unnoticed Monument to One Man's Human

Kindness

Harlingen, Texas, where Frank lives, has a population of

50,000, of which 40,000 are Mexican-American. It is at the

center of the Rio Grande Valley. It likes to call itself the

hub city of the Valley. Some ten miles from the Border, as

the crow flies, its economy lies deeply rooted in the sur-

rounding agriculture.

Go north on 7th Street, past Andy's Model Market,

across the 77 Sunshine Strip by-pass. On the east are the

practice fields of Harlingen High School. On the west, a

few low-income houses soon give way to three ultra-

modern, magnificent churches of different denominations.

A half mile farther north, on the west side of the paved

road, is Frank Ferree's shack, the poorest of the poor,

where unscheduled helpfulness is the order of the day.

I have seen his response to the needy. Once, in leaner

times, I mentioned casually that my typewriter was worn

out, making it very hard to turn out free-lance newspaper

articles.

To my great surprise and astonishment, a day later one

of Frank's helpers delivered an ancient, but perfectly usable

typewriter. It seems that years ago when one ol the local

railroad freight offices restocked with new typewriters,

-- 57 --

Frank had taken the old typewriters off their hands and

stored them away in his shack, waiting for someone to need

one.

Across the highway and east of Frank's shack lies open

crop land. The Harlingen airport, formerly Harlingen Air

Force Base, is located a couple ot miles away.

The tall brown grass sways in the Gulf breezes around

Frank's house. A dozen salt-cedar trees provide shade, their

sharp, needle-like leaves sighing constantly in the wind. It

sounds as if the souls of all the world's needy and desperate

are collected in the air around Frank's dwelling, crying out

their sadness, their frustrations their hopelessness.

To the south and across the dirt road can be seen the

bare shacks ot the poor. Thev were built on lots provided

from some of Frank's original twenty-three acres.

Just north of his shack are the remains of the old mas-

sage studio which he now uses for storage. In front of this

stands a large concrete monument and plaque facing the

highway. A few citizens of the Valley recently erected this

monument and placed a floodlight to shine On it at night.

The insciption on the monument reads:

"Inasmuch as you have done it to the least of these

my brethren, you have done it to me." Matt. 25:40.

"Headquarters site for Volunteer Border Relief. 1943.

Incorporated to extend free and voluntary aid to the home-

less, the hungry and ill Border residents who care."

Few passers-by even see the monument. Fewer stop to

see what it says. Fewer than that understand what it really

says.

Do-gooders seldom produce revenue. They seldom can

be exploited by commercial interests. There's simply no

monetary profit to the commullity, to the con-artists and

wheeler-dealers.

So an old man does good. Fine, but what's in it for

me? Where's the money angle? Now, you take a tourist-

trap a carnival ride, a sideshow, these you can promote,

these you can exploit, take the suckers to the cleaners, strip

-- 58 --

them of all they've got. But a harmless old man who goes

about doing good?

Several bodies of worn-out trucks rust in the yard.

Scraps of packing cases, cardboard hoxes pressed flat and

stacked neatly, are in front of the house, ready to be loaded

on the truck to be hauled to those who can build shelters

from them.

A large and ancient food refrigerator stands beside the

front door. Here Ferree stores soup bones and interior

meat cuts that can't be sold. Nothing is wasted.

An outside phone rests beneath a crude home-made

box covering to protect it from the elements. The porch is

crumbling. The front door has been off its hinges for years,

long gone to "someone who needed it" more than he. A

hole in the floor is now covered with a piece of plywood,

since one of Frank's visitors fell through it.

He's cleaned up the place somewhat from the utter