The second commissioning on 27 October 48. Photos courtesy of Melvin Blank. Note the former "skippers" Schoeffel and Smith in attendance.

~ 128 ~ [diagram - longitudinal cutaway]

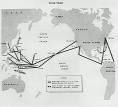

Points of interest aboard the Cabot Displaeement 14,800 tons Overall Length 610 feet Beam (Extreme) 109 feet Draft (Average) 24 1/2 feet Height Flight Deck Above Water 44 1/2 feet Height Navigation Bridge Above Water 55 1/2 feet Length Of Flight Deck 552 feet Width Of Flight Deck 73 feet Aircraft Crane (7 Ton Capacity) l Aircraft Elevators 2 Boilers 4 Turbines 4 Propellers ( 16~ diameter) 4 Horsepower 100,000 Fuel Consumption (Normal Cruising Speed) 60 Gallons Oil/min. Fresh Water Distillation 40,000 Gals/day (source) CNATra-P&PO-PNAS-1069-(6-6-49)-10M Track Chart [map of Pacific and Western Hemisphere]

~ 129 ~ [picture of Cabot from the air]

Secretary of The Navy For Sir John F. Floberg lands on board the Cabot in a SNJ-5C on 18 April 1955. [picture of Cabot from the air]

SNS DeDalo (PH-01) ex-USS Cabot (ATV-3) aerial stern view off port side 25 Aug. 1961. ~ 130 ~ [picture]

Ceremonies incident to the formal transfer of the USS Cabot to the Spanish Government in 30 August 67. Presentation of plaque to Master Peter D. Dunbar (a grandson of former Cabot Commanding Officer, W. W. Smith) by Capt. Elizalde. ~ 131 ~ [picture of a large group of men]

Audience with Pope Pius XII in the Vatican Palace. Cmdr. Larry W. Battle in front of the statue in right background. [picture in front of building with columns]

St. Pietro Cathedral - St. Peters Cathedral (Vatican Dome in the background) Photo courtesy of Cmdr. Larry W. "Rip" Battle. ~ 132 ~ (end of chapter 15) ========================== . CHAPTER SIXTEEN "THE CVL's SUCCESS STORY" by Lieutenant Commander A. Halsey, USN "Reprinted from Proceedings by permission: copyright (1946) U.S. Naval Institute It was a gloomy gray morning only a month and three days after Pearl Harbor. Three United; States carriers, Wasp, Yorktown, and the brand-new Hornet, were hurrying from the Atlantic to the Pacific battle zones. At Norfolk Navy Yard the first of a mighty class of flat- tops, U.S.S. Essex, was still more than a year from battle readiness. Available against superior Jap carrier forces which already had blooded their bombers in the sneak attack were only two carriers, Lexington and Enterprise. There had been a third, the proud Saratoga. Now she was limping back to Puget Sound Navy Yard with one flank laid open by a long torpedo wound-a five-month repair job. The day of plane-fought naval battles like Coral Sea had not yet dawned. But wise heads in the Navy Department could already see the smoke-etched outlines of titanic carrier struggles to come. And the immediate need for carriers was desperate. On that morning, January 10, 1942, the New York Shipbuilding Corporation at Camden, New Jersey, was racing ahead on one of the world's largest programs of cruiser construction. On one ship, there suddenly came a pause. Orders had just been received to convert the light cruiser Amsterdam into an aircraft carrier. A cruiser into a carrier? New York Ship executives clamped down hard on their pipe stems. It had been done only twice before in American shipbuilding history. Back in the twenties, the Saratoga and Lexington were converted from 45,000-ton battle cruisers to 33,000-ton carriers by New York Ship and the Fore River Shipbuilding Company at Quincy, Massachusetts, respectively. Those, however, were leisurely peacetime projects. The Saratoga, laid down in 1920, was ordered altered to a carrier in 1922 under limitations imposed by the Washington Treaty. She was not completed until November 16, 1927, a full five years later. Now, under pressure of war, there was not time for prolonged planning and slow, painstaking construction. A job had to be done "chop- chop!" And chop-chop it very nearly was. The Amsterdam's keel had been laid on May 1, 1941, under a peacetime contract calling for her delivery as a cruiser two and a half years later on November 15, 1943. Subsequently the New York Shipbuilding Corporation speeded up the job to keep step with the quickening pace of the European war. By January of 1942, her hull was constructed up to the main deck level. Barbettes, ammunition hoists, and other gunnery ship features were installed or partly installed. Her smoke pipes were trunked for the usual twin cruiser stacks. Ironically, results of the speed-up in the cruiser now took the form of I obstacles to the carrier conversion job. Before I much could be done on it, some work had to be undone. Acetylene cutters and metal workers pitched in. Ammunition hoists and barbettes for 6-inch guns had to come out, fast, for there would be no room for such big turret guns in a carrier. To wall off her high-octane gasoline, a carrier requires heavy bulkheads across the ship at points where they are not ordinarily needed on a cruiser. In building carriers from the keel up, such bulkheads usually are installed in one piece or in large sections. On the Amsterdam, however, completion of the second and third decks had sealed up all openings large enough for the bulkheads to be lowered through. To ~ 133 ~ avoid ripping up the decks, the shipyard had to install the bulkheads slowly bit by bit. There were questions and problems galore. One of the most sensitive involved piling a lofty flight deck atop a hull not planned to carry such a burden at such a height. In the language of naval architecture, this gave the ship a "higher metacentric center." In other words, she was more likely to roll sidewise and even to tip over. Usually such problems are worked out by studying scale models of the ship floating in a model basin. Now, however, there was not time even for that. Two schools of thought sprang up. One favored ballasting the ship to bring her lower in the water and make her stiffer. It was calculated that this would require 6,000 tons of ballast. The burden of added weight would have cut the ship's speed. And every knot of speed can prove precious in launching planes in the light breezes of the Pacific. So the other, more novel proposal won out. It was to steady the ship by broadening her. It called for the construction of blisters or bulges on both sides. These were to extend beyond the normal sides of the ship for 31/4 feet amidships and were to taper down to nothing near the bow and stern. Then it was discovered that the additional tonnage of the superstructure or island, all on the extreme starboard side, needed compensating weight on the port side. So a moderate dose of cement was poured into the port blister. This ended happily what has since been nicknamed "The Battle of Ballast versus Blister." It was far from the last of the CVL's battles, in design and drafting rooms or in the combat areas. Was there room for only one plane elevator, aft as in the first of the escort carriers, the little Long Island, converted from a merchant motorship the previous June? Or could a forward elevator be squeezed in, too? Where should the island be located? And what about stacks? How many guns could she mount, and where? How far forward should the flight deck be carried. The Bureau of Ships came through with its ideas on the subject in quick order. There would be two elevators, making for much faster handling of planes. The island, held to a cramped minimum in size, would be about a third of the distance aft and conventionallY on the starboard side, with a maze of ladders and catwalks outboard below it. The stacks would be four in number, square instead of round, and trunked out and up at right angles to the ship. There would be one main gun mount aft, on a sponson projecting from the stern, and another forward. Forty and 20-mm. anti-aircraft guns would be mounted in galleries just below the flight deck level. The flight deck would be carried from the very stern to within about 50 feet of the bow. To have brought it all the way to the stem would have overloaded that knife-edge of a cruiser bow; therefore it was very wisely avoided. New York Ship went to work with a will, as was its way. Up above the main deck climbed the bulkheads of the hangar deck. Atop went the flight deck. As the upper works soared and added tonnage by the hundreds displacement factors trembled as delicately as a grocer's scales during the meat shortage. Every small sacrifice of weight counted. A typical one was the elimination of all doors to officers' quarters. Gray cloth curtains took their places. Workmen on other ships, uninformed of the conversion, were just beginning to gape at the weird goings-on aboard the Amsterdam when New York Ship received further word from the Navy Department on February 16, 1942. Convert the cruisers Tallahassee and New Haven into two additional carriers, it said. Again the din and furor increased. Now all the specifications and blueprints, material, and carrier gear for the ex-Amsterdam had to be multiplied by three. Fortunately the Tallahassee had been laid down a full month after the Amsterdam, and the New Haven a good two and a half months after that. Not as many structural alterations were necessary. Work went on apace. The latest orders were the upshot of a buzz of conference and telephone talk in the Navy Department's high places and with New York Ship executives and the Navy Supervisor of Shipbuilding at Camden. Behind it was the conviction that the carrier was destined to play an even greater role in the Pacific war. Vice Ad- ~ 134 ~ niral Halsey with the Enterprise and Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher with the Yorktown lad just swept through the Jap-held Marshall md Gilbert Islands in a heartening series of successful hit-run raids. There was already protected a highly secret and daring carrier air strike, later to ring around the world as the attack on Tokyo in April, 1942. Within a month came more orders: On March 18 to convert the proposed cruiser Fargo and three days later to convert the Huntington and Dayton. Now the total of the cruiser - carriers, as they were being dubbed, stood at six. It was a sizable hunk of the big shipyard's construction program. Moreover, some of it was very fresh and new. Huntington had been laid down only 17 weeks earlier. There were no great conversion problems there. Dayton's keel was placed on the ways only 12 weeks before the orders came to convert her. But Fargo's story topped them all. Originally awarded to another shipyard, the orders to convert her came through on the very day that her keel was laid. And thus the problems of planning and supply were multiplied by six. The cruiser-carriers held the highest priorities in the humming shipyard at that time. The justification came soon and grimly. On May 8, 1942, in the far-flung battle of the Coral Sea, that giant carrier Lexington received her death wounds. On June 7, one day less than a month later, the wounded Yorktown gave up the struggle at Midway after a Jap submarine's torpedoes smacked into her and a destroyer alongside her. Carrier forces had won two great victories, virtually without a single exchange of shells between surface ships. But they had also demonstrated that carriers can kill carriers and that sea-air battles cannot be won without loss. The Navy Department lost little time in taking the hint. On July 11, 1942, New York Ship got its orders to convert three more light cruisers to carriers. This time they were the Buffalo, Wilmington, and Newark. Wilmington was four months along on the ways. Buffalo and Newark were not even begun. Work on them was not started for six weeks and three and a half months, respectively. The total stood at nine-nine of an absolutely new class of ships replete with all the headaches of hurried conversion and wartime procurement, the worst nightmares that can haunt a shipyard. Shoulders at New York Ship, from executives' to rivet heaters', were hunched hard at the job. But they were broad enough for the burden. Soon the names of the new carriers-to-be came through from the Navy Department. They were names resounding with the past grandeur of well-fought ships and hard-won battles. Amsterdam, first strange duckling of the conversion brood, was changed to Independence after a 10-gun sloop of the Revolutionary Navy, a 74-gun ship of the line of 1812, and a Mexican War blockader. Even more appropriately, the name honored Philadelphia and Independence Hall, just across the Delaware from New York Ship. Number Two, the Talahassee, became the Princeton, a proud name if not a lucky one. The first Princeton, named after the Revolutionary Battle near the University site, was the brain- child of the great Ericsson twenty years before his more famed Monitor made history. Princeton was the Navy's first screw-propelled ship, and first "all-big-gun" ship mounting heavy cannon along her center line. But one of the giant cannon exploded in 1844, killing the Secretaries of State and of the Navy and other bystanders. Princeton's II and III were Civil War and Spanish-American War gunboats. Princeton IV was to become the first of the Independence class to be sunk in action, nearly three years later off the Philippines. On down the line of ships building on the ways ran the changes. New Haven became Belleau Wood after the Marines' famous struggle of World War I. Huntington became Cowpens after the Revolutionary victory. Dayton and Newark were renamed Monterey and San Jacinto after the Mexican War battles of nearly a century earlier. Fargo snatched up the fine old name of Langley, inherited from the venerable plane tender which the Japs had sunk off the Netherlands East Indies a few months before. Buffalo emerged with perhaps the proudest and most heroic name of all-Bataan, still a fresh heart-ache over America. She ~ 135 ~ lashed out to sea later as a symbol of the joint vengeance of the American and Filipino peoples, with a personal Godspeed from President Quezon and Vice President Sergio Osmena. The work could not go too fast to suit the Navy. On August 22, 1942 the Independence slid into the Delaware. First of the class, she was launched as a carrier less than 16 months after she was begun in peacetime as a cruiser. As if to taunt the shipyard on its success, the Japs sent the big Saratoga limping back to Pearl Harbor for repairs the very next week. Three weeks later, a spread of Japanese submarine torpedoes spanked into the U.S.S. Wasp off the Solomons. She burned furiously and soon was beyond saving. The ever present need for carriers grew really dire. On October 18, 1942, New York Ship launched the carrier Princeton, second of the class and another 16-month job. Exactly eight days later, the Japs fatally wounded the haughty Hornet in the sea-air inferno called the Battle of Santa Cruz. Now the carrier forces of the United States Navy were down to one ship, the indefatigable Enterprise. And the "Big E," having absorbed six bomb hits in two months, was far from unscathed. Never did the urgency for carriers seem greater or the Navy's means of holding the Pacific look slimmer. And New York Ship appeared to be losing its private race to build flat-tops faster than the Japs could sink them. Labor scouts scoured the countryside for welders, riveters, electricians, metal smiths, and painters. Man power was poured through the shipyard gates to hurry ahead on delivery schedules. In December of 1942 they launched the Belleau Wood, a third of the nine stopgap sisters. On January 14, 1943, there would have been ample excuse for a celebration if time could have been found for it. On that day New York Ship delivered the aircraft carrier Independence to the Navy ten months ahead of the contract date for her completion as a cruiser. Here was the proof. It could be done. But it remained to be done again, eight times over. Launchings and deliveries began to alternate like left-right punches at the enemy. They launched the Cowpens three days after the Independence slipped over the Philadelphia Navy Yard for commissioning. They delivered the Princeton on February 25 and launched the Monterey three days after that. They delivered the Belleau Wood on March 31 and within four days sent the new Cabot down the ways. They launched the new Langley on May 22 and delivered the Cowpens on May 28. On June 17 the Monterey, smart in her fresh paint, was delivered. On July 24 the Cabot followed her out. On the first day of August the Bataan was launched and on the last day of August the Langley was placed in ready Navy hands. The San Jacinto, youngest of the nine sisters, went down the ways on September 26. Bataan was commissioned on November 17 and San Jacinto on December 15 after a remarkably fast outfitting of less than three months from her launching. And that completed the list. Every one of the nine was in commission before the end of 1943. To take in the full measure of this shipyard miracle, it is necessary to study the nine-ship project from the start. The Navy Department gave New York Ship the nine contracts during the latter half of 1940. France had already fallen, Britain stood alone, and the imminence of American involvement in the war was well known. Thanks to continued warship construction during the peacetime doldrums, New York Ship was as highly geared to produce combatant craft as any yard in the nation. Yet the best it was expected to do was to turn out the first of the nine cruisers by the end of 1943, three more in 1944, four in 1945, and the final one in 1946. As it was, New York Ship delivered the last of the nine carriers within one month of the original date set for delivery of the first of the cruisers. The best time was made on the Cabot, ex- Wilmington, a total of 27 1/4 months cut from the contract schedule. The yard cut its working time 26 1/2 months on the Monterey, 26 1/4 months on the San Jacinto, 25 1/2 months on the Bataan, 25 months on the Cowpens. Thus the builders beat the original schedule by better than two years on five of the nine. The ~ 136 ~ other four timesavings ran 13 1/2 months for Belleau Wood, 12 3/4 months for Princeton, 10 months for Independence, and 9 1/4 months for Langley. The carriers were coming. They were coming on larger numbers than the empire-snatching Japs ever dreamed America could produce them. When a shipyard's woes with a ship are over, the Navy's are just beginning. The precarious push of producing aircraft carriers like eggs out of a magician's hat did not stop at the commissioning stage. For a ship without a seasoned crew is no more than a partially completed machine. Every one of the nine CVL's was commissioned at the Philadelphia Navy Yard the lay she arrived there. All told, they required more than 12,000 officers and men over a tenth of the entire Navy's strength four years earlier. Much of the personnel proved to be almost as new to the navy as the ships themselves. The "keels" of the crews were laid earlier in the form of precommissioning details at the old red brick Welsbach Building on the southern edge of New York Ship's sprawling premises. Engineer and warrant officers usually reported first to familiarize themselves with machinery and electrical installations from the early stages. Then the captains and execs would "come aboard" to desks in the Welsbach Building. Then division officers and chief petty officers. As the ships grew on the near-by ways and later in the wet basins, the skeleton crews took on flesh. As a rule, the final drafts of hundreds of enlisted men reported from "boot" camps and receiving stations on the very morning of the commissionings. The thin red-and-white-striped commission pennants with the blue stars went up over salty scatterings of weather-tanned sailormen wearing officers' gold or petty officers' "crows." But the bulk of the man power on each ship would be one of the biggest and best collections of clerks, haberdashers, soda jerkers, bell hops, high-school athletes, and farm boys who ever squared a white hat on their heads and tightened their jaws in determination to look at home in Navy blues. It is not on record that any cruiser carrier drew even half a crew familiar with the sea. On putting out from the Delaware Capes into the rolling Atlantic for the first time, some introduced over 70 per cent of their entire ship's companies to the ocean for the first time. Often the resulting relationship was intimate and unpleasant. Shakedown cruises usually began with shakeups of epidemic proportions. One CVL rammed into a gale which tossed solid water over her heaving flight deck, nearly 50 feet above the sea. According to scuttlebutt, 80 per cent of those aboard suffered gastronomic losses. The ailment was no respecter of persons, as usual. The exec fell victim along with the boots. Only a third of the wardroom mess showed up for meals, but the mess could not economize by it; flounding messboys broke more than enough china to offset the value of the unwanted rations. Among the officers, the personnel situation often tended to make a "trade school man," as disrespectful reserves call the Annapolis graduates, feel like an outsider in his own Navy. The captains of all nine CVL's were, of course, seasoned Naval Academy graduates. Next to each came the executive officer and eight heads of departments: air, engineering, gunnery, damage control, navigation, communications, supply, medicine. As a rule, not more than five or six of these were Naval Academy scions. And nearly all officers below them, that is, nearly all below the rank of Commander or Lieutenant Commander, were reserves. One ship went to sea with 15 per cent of its officers from the regular Navy and the remaining 85 per cent reserves, some of them without previous sea experience. Aside from the department heads, who do not stand deck watches, there were only four officers qualified to serve as officer-of-the- deck under way-that is, to supervise the routine of running the ship at sea. One of these four was a "trade school boy"; one was a former enlisted man who worked up to a commission, and the other two were reserve officers. Until other officers managed to qualify, these four stood "heel-and-toe" watches one after the other, without a letup. To the great ~ 137 ~ credit of all concerned, the ship got along smartly to her destination. The captain heaved a sigh of relief like a stream whistle, though, when they let go the hook in port. All in all, the debut of the cruiser-carriers made for a very sporting venture on the part of some of the gamest skippers who ever conned a flat-top. The problem of command combined an untried type of ship, new and sometimes inexperienced officers, freshman fliers, and some of the largest ladlings of green enlisted men that the wartime Navy ever tried to digest at one gulp. To top it off, there were the new planes. The Independence and the first of her sisters, Princeton and Belleau Wood, steamed forth just in time to receive one of the aviation gods' greatest gifts to a flying Navy: the Grumman F-6-F fighter plane, now famous as the "Hellcat." Up to that time the fastest carrier- borne fighter in general use was the F4F "Wildcat," a 1,200-hp. job with a top speed of about 300 m.p.h. Now along came big brother. The "Hellcat" harnessed 2,000 hp. in its one mammoth engine and was credited with over 400 m.p.h. Its landing speed, principal concern of the carrier men, was considerably higher than the Wildcat's. By every standard, the Hellcat was a "hot" ship to fly and a hotter one to land. Even the larger carriers, with 100 feet or more of flight deck than the Independence, were none to large for the oversized fighters. As for the Independences-one former Wildcat pilot said after his first landing on one in a Hellcat, "It felt like hitting a splinter with a bolt of lightning." The Hellcat was a real gift-horse, but it took a lot of gall to look its 2,000-horse engine the the teeth. The CVL pilots, mostly reserve officers without previous carrier experience, warmed up for the ordeal with Wildcats aboard the small escort carrier Charger in the Chesapeake. After they made the grade there, they were ready for the larger CVL's and their stampeding stallions of the air. All did not go perfectly at the start. Nearly every one of the nine slender sister-ships suffered losses of planes and personnel on their shakedowns. In at least one instance, the operational (non-combat) loss of planes on the shakedown amounted to 25 per cent. There were more than a few occasions when Hellcats, coming in too fast or too high, overshot the arresting wires and smashed into the stout, waist-high barrier cables more than half-way down the flight deck. Some nosed over with their propellers madly flailing chips from the decks. Some ripped loose the cables and wrapped them in a crazy tangles around their propellers. Marvelous to behold, the pilots usually climbed out of their cockpits unscratched. Air-borne successors of the wooden ships and iron men, these aluminum craft were blessed with men of steel. Luck did not always hold, however. One pilot circled and swooped for a landing just as his carrier's stern rose on a swell. The plane tailhook caught in the after edge of the flight deck, snapped, and spun forward in a high arc above the plane. The plane raced unchecked across the deck, suddenly it veered wildly to one side and struck a group of enlisted men of the flight deck division. One was pitched into a net and caught there while the plane burned above him. He died. Two others, knocked into a choppy sea, never were seen again. Five or six more were slightly injured. The pilot jumped out one second ahead of the flames, unhurt except for a gashed forehead. Three weeks later, he was flying again. A thin, dark youth with a faint trace of black mustache, he subsequently died a hero's death in one of the first air strikes at the Bonins. On another CVL shakedown, one of the big F6F's damaged its right wheel in attempting a fly-away take-off. It slued to the right and ran off into the sea over a 40-mm. gun mount forward of the island, causing some casualties and putting the guns out of commission. But accidents were the exception. They usually were the inevitable result of the combination of new ships, new planes, new personnel, and ceaseless driving to prepare for Pacific combat. That was the goal. Every man in the fledgling carriers kept his eyes on it. September 1, 1943, was nothing more than the Wednesday before Labor Day in the United States. In the Pacific it was a more noteworthy date for several warlike reasons. It marked approximately the opening of the sledge-hammer ~ 138 ~ i offensives from the air by which United States carrier forces softened archipelago after archipelago of Pacific islands for invasion. and three of a strange new breed of warships struck at the enemy for the first time that day. Their planes hit so hard and clean and fast, batting down enemy aircraft far from the carriers themselves, that months passed before the Japs came to recognize the cruiser-bowed flat-tops with their four stumpy stacks as a fresh trademark of "Made-in-USA" naval might. Three of the new light carriers went into action for the first time exactly one year and one week after the Independence, first of the class, was launched. Princeton and Belleau Wood teamed up to execute a mission all their own, escorted by four destroyers and auxiliary craft. This was to provide air cover for the landing of U. S. troops on Baker Island, a strategic sandspit southwest of Hawaii on the fringe of the area then dominated by Japan. As luck had it, there were no Japs on the island. The landing was unopposed. But the CVL pilots took their big new Hellcat fighters into action for the first time that such planes were used in combat in the Pacific. Appropriately, the Hellcats' first prey was an equally new type of Jap plane, later given the homely nickname of "Emily." The first "Emily," a four-engined patrol bomber, stuck her inquisitive nose over the horizon on September 1 just as the Baker Island occupation was getting well under way. The Hellcats gleefully tore her apart and sent he sizzling into the sea. Two more Emilys were pommeled apart on September 3 and September 8. Hellcat cameras also caught the new bombers and furnished the fleet with its first pictures of them. Independence meanwhile set out on a party of her own with two bigger carriers, a battleship, and 13 cruisers and destroyers. This task force went loaded for big game but its luck was poor. It bombed and shelled Marcus Island. The operation revealed one big future role of the CVL's to provide "combat air patrols" or air cover for task forces while the bigger carriers sent their planes inshore to bomb and strafe. Independence fliers flew 48 of the 56 CAP sorties made at Marcus. Nearly a year later, the Navy Department was to pay tribute to this sort of service in a press release outlining the functions of the light carriers. It said in part: Airmen from a light carrier join up with the larger air group from a big carrier to add a greater punch in a strike upon enemy shipping or islands. Or the light carrier's pilots assume the vital job of protecting the task force against enemy attack, thus freeing the larger carriers' planes entirely to concentrate upon the mission of assault. Some of the interceptions accomplished by protective planes from the light carriers have been spectacular; entire formations of attacking Jap bombers have been shot down before they could even get within sight of the fleet. There is a plain, mathematical measure of what the addition of the three light carriers meant to our carrier strength in the fall of 1943. At that time, we had in the Pacific the Saratoga and Enterprise, oft-wounded veterans, and four new Essex-class carriers, Essex, Lexington, Yorktown, and Bunker Hill. The total stood at six first-line carriers. To be sure, there were escort carriers on hand. But these were thin-skinned 20-knot ships, unable to keep pace with a fast task force or to withstand the battering it might receive. The three CVL's, armored and compartmented in warship style, could step along a better than 30 knots. Although they lacked the plane capacity of the larger carriers, they were fit company for them in every other respect. They increased our fast carrier units by 50 per cent. Their timely arrival made possible the organization of new and numerous carrier striking groups. The Princeton and Belleau Wood lined up with the bigger Lexington to hack at Tarawa on September 18. Lexington planes bombed the island four times. Fliers from the two light carriers merged forces and made two strikes on Tarawa independently of the Lexington pilots. Early in October the brand-new CVL Cowpens arrived to combine with the Independence, the Belleau Wood, and the Essex-class carriers Essex, Yorktown, and Lexington in giving Wake Island a thorough 48-hour trouncing. Cowpens pilots pitched in enthusiastically and suffered a loss of eight fighter planes, five shot down and three cracked up. By contrast, Independence luck ran strong. Without losing a ~ 139 ~ single plane, her pilots downed six Jap planes in the air, destroyed two more on the ground, wrecked anti-aircraft batteries and an ammunition dump, damaged an enemy destroyer escort, and showered 11,600 pounds of bombs on nearby Marcus and Peale island installations. Combat air patrols from Independence and Belleau Wood routed six twin-engined Jap bombers and six fighters with losses to the enemy. With the arrival of the Monterey, fifth of the class, in November, the light cruiser-carriers were slashing far and wide over the Pacific. Princeton once steamed an estimated 12,500 miles in less than three weeks to carry out a string of attacks. Independence and Belleau Wood each figured in four major operations between September 1 and November 18. Late in November came the biggest carrier assault of the war to date. Six Essex carriers and all five of the light carriers tore through the Gilberts and Marshalls, wreaking devastation ashore and afloat. The Independence's luck, stretched thin, broke on November 20. At 5:58 p.m., her planes overhead reported 15 to 18 twin-engined Jap "Betty" bombers headed for the ship with torpedoes. Two minutes later they skimmed in just above wave level with the setting sun at their backs. Anti-aircraft thumped down seven in a few roaring seconds. The planes overhead swooped down and accounted for four more. But one circled and sent his "fish" tearing into the Independence's starboard side just nine minutes after the attackers were first sighted. Her speed slumped to a sickly 4 knots. She barely dragged along for an hour. Then her crew got her going again. First of her class to be hit, she reached port safely under her own power. In the grim ratings of the lower decks there are "one- torpedo ships," "two-torpedo ships," and so on. The Independence remained afloat after one torpedo hit. Automatically, the light carriers were rated "two-torpedo ships" or better. And their stock went up accordingly. The cruiser-carriers were blooded and proved. They could steam as fast as the big boys. They could fight off air attacks with their guns and planes. And they could take torpedo punishment-the worst punishment a ship risks. At one time during the watery campaigns of 1943-44, the ex-cruisers formed fully half of the Navy's fast carrier forces in the Pacific. The CVL's figured prominently in the epic sweeps of Task Force 58, which ranged up to the harbor gates of Tokyo. Tarawa, Makin, Buna, Buka, Rabaul, Kwajalein, Eniwetok, Truk, Yap, Palau, Hollandia, Guam, Saipan, Mindanao, Luzon, Formosa, Manila, Hongkong, Iwo Jima, Tokyo, Okinawa-the carriers with the cruiser bows stuck their sharp noses into all of them. On an average, they participated in ten to twelve major engagements. They drove through the endless wastes of the Pacific for something like 200,000 sea miles apiece. They saw air groups, which burn brightly with a short-lived flame, come and go but the carriers and their crews seemed to go on forever. They accumulated barnacles and sea moss, casualties and medals, lethargy and legends. There was the U.S.S. Cabot, nicknamed "The Iron Woman" because she fought through every big sea-air battle of 1944 and 1945 and accounted for nearly 250 Jap planes and 30 enemy ships. Her planes pommeled Jap battleships and cruisers in the Battle for Leyte Gulf. When the fast carrier force made its bold sweep of the China Sea, the "Iron Woman" was the first ship in and the last one out. Detailed to a "death watch"-the slow, dangerous duty of escorting two large damaged ships to safety from close by the Jap stronghold of Formosa-the "Iron Woman" unflinchingly mothered her maimed charges. Her fighter planes smashed two enemy air attacks on the cripples. In one, eight of her Hellcats downed 31 attacking Jap planes. Her Avenger pilots threw three torpedoes into the Jap superbattleship Yamato, last of the newest Nip battlewagons. " Yamato now squashed tomato, so sorry," one flier is said to have radioed as the 45,000-ton ship turned turtle. There was the air group nicknamed the "Sun Setters," because their aim was to down the "Rising Suns." Their aim was good: 81 planes and 38 ships in one eight-month cruise. There was another group, the "Meat Axes," so called because they slashed down Jap planes bearing ~ 140 ~ the round red "meat ball" insignia. Lieutenant William E. Henry, exec of "Fighting Forty- One," another CVL air group, became probably the Navy's foremost night fighter by intercepting and downing seven Jap planes in the dark. His night interception of a four-motored Jap bomber is the shortest recorded-17 minutes from carrier take-off to the time he reported: "Splash one Emily! " The CVL fliers were unorthodox and resourceful. When three Avenger pilots from the U.S.S. Bataan spotted a l,900-ton Jap freighter off Saipan, they were on anti-submarine patrol, carrying only depth charges. Lacking bombs or torpedoes, they devised a means of setting the depth charges to explode "just right," as one of them put it. It was "just wrong" for the freighter, which promptly sank. Air Group Forty-Five flying from another cruiser-carrier, slowed down the suicide business at Okinawa when 16 of the Hellcats downed 21 and one quarter Jap planes in one hour flat last April 6. The quarter plane was shared with other fighters. "We chopped 'em up that fine," the squadron leader explained. Four torpedo planes from the Princeton, now dead and buried in the depths off the Philippines, rivaled the fatal heroism of famed "Torpedo Eight" at Midway in attacking a big Jap carrier without fighter protection in the Battle of the Eastern Philippines, June, 1944. They struck alone in the waning twilight at an extreme range of 250 miles from their ship. It was that or let a 28,000-ton enemy carrier of the Hayataka class escape into the night. From all indications, she did not escape. The four planes reported three certain torpedo hits, followed by racking explosions. As night shut down, the Jap was so far down by the bow that her propellers were churning the air. Only one of the Princeton's torpedo planes got safely home. But the men of the others, luckier than Torpedo Eight with its sole survivor, were rescued from the sea later. Before the Japs got her last October, the Princeton fought 13 major battles. None were one-punch fights. She operated off Eniwetok for nearly an entire month, for example. On her last day, ship and men were among the foremost veterans of the Pacific struggle. Ironically, a single Jap dive bomber sneaked out of a low cloud and dealt a fatal wound before the panting anti-aircraft guns could down it. The Jap pilot probably never knew what hit him. For purposes of any record that Tokyo may care to keep, it was a fighter plane from another cruiser-carrier, piloted by Commander Malcolm T. Wordell, of Rumford, Rhode Island, skipper of Air Group Forty-Four. It was Wordell's second plane that morning. The CVL's avenged their own. In addition to sinking or damaging an impressive tonnage of enemy shipping, the CVL's are officially credited with destroying 2,569 Jap aircraft, a fair-sized air force in itself. Of these, 1,295 were knocked down in the air by CVL planes and anti-aircraft guns. The remaining 1,274 were blasted apart on the ground. The ratio of air and ground destruction in itself offers an interesting index to the course of the war. Some of the first ships out got more planes in the air, some of the latter more on the ground as the Japs softened. High scorer was San Jacinto, last of the CVL's, which nailed 150 of its 459 Jap planes in the air and 309 on the ground. Cabot, operating furiously from scratch, shot down 254 of its 330 victims on the wing. The official records give Belleau Wood 440, Cowpens 317, Monterey 302, Langley 250, Princeton 194, Bataan 162, and the torpedo- damaged Independence 117. A naval cycle was completed last July 8 at the Camden shipyard where the nine make-shift sister-ships were born. There they launched the first of a new class of "bigger and better" light carriers, the U.S.S. Saipan. A second, the U.S.S. Wright, followed later. Appearance of the class was regarded as a form of accolade for the earlier CVL's: ships of a given type and size are not continued unless successful. The Saipan hulls are built to heavy cruiser specifications. They displace approximately 14,500 compared with 11,000 tons for their predecessors. However, they retain many outward characteristics of the Independence, including small islands and four trunked stacks. If further proof of the arrival of the CVL in ~ 141 ~ naval circles need be cited, one may turn to the British Navy. His Majesty's most modern ships now include an entire class of carriers akin to the Saipans in size, speed, and other characteristics. Known as the Colossus class, these ships are approximately 700 feet long and displace 14,000 tons. One, H.M.S. Powerful, is known to have been launched at Belfast as far back as last February 27. Another, H.M.S. Leviathan, was christened at Wallsend June 8 by the Duchess of Kent. In appearance the class, descended from the experimental light carrier Unicorn, resemble larger British carriers rather than American light carriers. They have the typical single stacks, tripod masts, and flight decks faired into the hull fore and aft. But in general type and function the British and American ships undoubtedly are cousins. To conclude, the wartime American CVL's were frankly a desperate experiment. The experiment succeeded. As nearly as it can be said of anything in a changing atomic world, the CVL seems to be here to stay. Reprinted from Proceedings by permission Copyright (c) (1946) U.S. Naval Institute. ~ 142 ~ (end chapter 16) (Appendices follow)